|

MANCHESTER, NH AIRPORT

(MHT)

The World War Two Years

by

Tom

Hildreth

Manchester Airport in southern New Hampshire has grown to

become one of the leading regional airline facilities in the country. The

modern terminal and parking garage are both due to receive additional

expansion, and recently completed improvements to runway 6-24 will now

enable extensive work to continue on runway 17-35 which is the airport's

longest. In the year 2000, 3.5 million passengers were expected to use

this southern New Hampshire airport, which has successfully capitalized on

congestion and surface transport problem at Boston's Logan Airport in

Massachusetts. Recognizing the potential in this market, airlines serving

Manchester are providing larger, quieter and more modern equipment such as

the Boeing 757 and Airbus A320. Nearly 100 airline movements per day

support these burgeoning passenger operations, which now include flights

to Canada. Executive aviation has seen a boost in the form of the large

new facility operated by Wiggins, located on the east side of the long

runway opposite the new airline terminal.

During a crucial part of

World War II, this airport was for the primary staging base for heavy

bombers en route to the war in Germany. The North Atlantic Wing of the Air

Transport Command, which was headquartered not far away in Manchester, ran

this massive airlift operation. The sharp-eyed traveler today can still

catch a glimpse of the airport's wartime history. A group of wooden

two-story barracks still exists in the southwest corner of the property,

not far from the UPS and Fedex facilities. Located among the tall pines in

this area, these remnants of Grenier Army Air Field house a number of

small businesses.

The success of Charles A. Lindbergh in crossing

the Atlantic Ocean in his single-engine "Spirit of St. Louis" in 1927

sparked great interest in aviation worldwide. Manchester, like most

American cities, embraced the aviation phenomenon with enthusiasm. On

August 25 of that year a loan was approved for $15,000 to establish an

airport in the Queen City. Construction of two 1800-ft. runways began on

October 25, at what became known as Smith Field. The airport saw gradual

improvement during the 1930s, including the federally-funded construction

of a hangar and administration building for $500,000. During this time the

runways were paved with asphalt. A Civilian Pilot Training program was

begun in 1939 under the auspices of the Civil Aeronautics Administration.

This led to a tremendous increase in flying activity at Smith Field. This

program was run by Granite State Airways, and more than 100 pilots were

turned out during 1939 and 1940.

As the war in Europe approached,

neutral America belatedly recognized the threat posed by the axis powers.

American industrial output rose to meet Allied demands for war materials,

and American and military planners recognized the need to expand our

meager network of military airfields. As far back as 1935, the Wilcox Act

recommended construction of several very large new military airfields. One

of these was to be located in the Northeast.

Manchester Police

Chief James F. O'Neil had been a strong supporter of aviation in the area,

and was one of the driving forces behind establishment of an airport in

the city. When O'Neil learned that federal officials were looking for a

location for a military airbase in the Northeast, he persuaded the Army to

investigate the development of Manchester Airport into the huge airbase

that was envisioned. Though the Army selected Chicopee Falls,

Massachusetts to be the site of the proposed Northeast Airbase, they did

not loose interest in Manchester. Transatlantic air travel was on the

rise, and the fog problem at the Boston and New York airports enforced the

belief that Manchester's inland location would provide a suitable

alternate landing site.

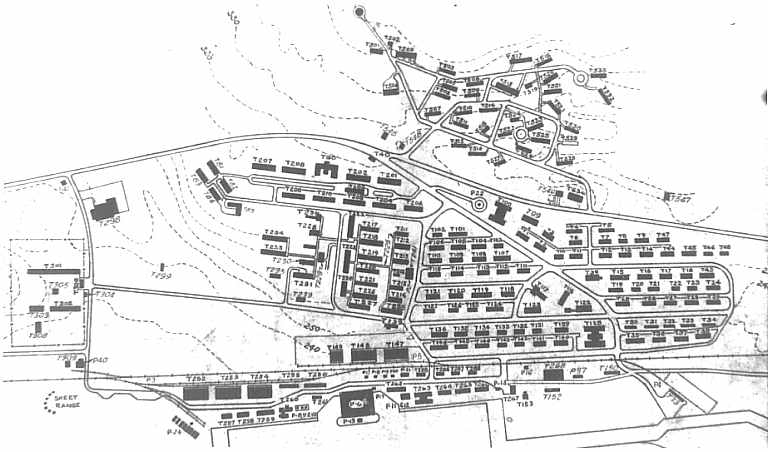

On October 3, 1940, the War Department

announced that the Manchester Airport would be developed as Manchester

Army Air Base. Expansion efforts began immediately. The Works Project

Administration (WPA) broke ground on October 7 under a $1.5 million

allotment for base construction. During December, work began around the

clock on the strengthening and expansion of the airfield's runway and

tarmac areas. The D.A. Sullivan Company, of Northampton, Massachusetts, a

firm that still exists today, and the Caye Construction Company of

Brooklyn, New York, began construction of 118 air base buildings in late

January 1941. The contract specified completion of the work within 90

days. These companies, working with the WPA, the Manchester Water Works,

and the Army Corps of Engineers employed approximately a thousand men

during the height of the construction phase.

Beginning in the dead

of a New Hampshire winter, the rapid construction of the base was a

remarkable feat. Heavy snow blanketed the site when the project began in

late January 1941, but by June the empty field had been transformed into

an airbase capable of housing more than 2,000 people. When Lt. Col. John

I. Moore arrived on April 1 to take command of the new airbase,

construction activities were in full swing. Runway and tarmac expansion,

begun in the fall of 1940, had continued through the harsh winter. Within

a week of Moore's arrival, the Caye Company had completed all 94 buildings

in their contract, and on May 7, the D.A. Sullivan Company completed the

24 buildings for which they were responsible. Utility connections to the

base were also being completed, and the Manchester Water Works and the

Works Project Administration (WPA) finished water and sewer connections by

April 21. An advertisement by the Public Service Company of New Hampshire,

supplier of electricity to the base, showed a formation of trimotor

aircraft flying over a power line and proclaimed, "So proudly we hail

Manchester's new Army Air Base..."

Officers from the 33rd Air Base

Group at Mitchell Field, Long Island arrived at Manchester to inspect the

air base project on March 5, 1941. Lt. Col. John I. Moore arrived on April

1 to take command of the base. The first military aircraft stationed at

the base, a single engine Northrop A-17 monoplane, arrived on April 25.

The 242nd Quartermaster Company arrived on May 20, bringing the first

troops to be assigned to the New Hampshire airbase. The 717th and 449th

Ordnance Companies arrived by truck convoy from Langley Field, Virginia

less than a week later. Members of the 45th Bomb Group (Light) under the

command of Lt. Col. George A. McHenry began to arrive by troop train and

truck from Savannah, Georgia, on June 18, 1941. Official Air Force records

show that this group was comprised of the 78th, 79th, 80th and 433rd Bomb

squadrons. Initially these units operated obsolete Martin B-10 and Douglas

B-18 bombers as interim training aircraft, until the arrival of the

Douglas A-20 Havoc later in the year.

By early July, the 125-bed

base hospital had opened its doors under the command of Capt. William D.

Willis, Base Surgeon. This facility was to be manned by a medical

detachment of 125 people with 1Lt. Bertha Elsner acting as Chief Nurse.

This hospital occupied fifteen different buildings, and would later be

designated as an Air Evacuation Center for war casualties returning from

combat in Europe.

Training of combat aircrew stationed at

Manchester required access to a practice bomb range, and in 1941 the

government acquired a plot of land near Joe English Mountain in New

Boston, New Hampshire. By the end of the year work had begun to establish

a bomb range in this hilly area 16 miles west of Manchester. Today, the

Air Force's New Boston Satellite Tracking Station stands on a portion of

the government property at this site, while the remainder of the range has

been converted to recreational use.

Capt. Frederick C. Bothwell, a

West Point graduate, commanded the 717th Ordnance Company (Aviation) Air

Base, and was assigned as Base Ordnance Officer. His assistant was Lt.

William J. Priest, who commanded the 449th Ordnance Company (Aviation)

Bombardment. Lt. Priest led all Ordnance personnel on a three-day exercise

to Bradley Field, Connecticut beginning on the 28th of August. The purpose

of the trip was to familiarize the men with truck convoy movement and to

study Ordnance functions involved in the supply and issue of material to

pursuit squadrons. At that time the 57th Fighter Group at Bradley was

operating Curtiss P-40 Warhawks.

Tactical and training activities

at Manchester were controlled by the 33rd Air Base Group and its component

34th and 35th Air Base Squadrons. Other units assigned to the base at that

time included the 1st Chemical Company, 17th Reconnaissance Squadron, 30th

Signal Platoon, and the medical detachment. By October the arrival of

small arms and automotive repair trucks allowed the Ordnance troops to

begin training in earnest. They had also completed construction of a skeet

range on base. An ample supply of practice bombs had arrived, which

allowed munitions personnel to learn their serious trade. On October 9 the

578th Army Air Forces Band was activated on the base. The original cadre

of four enlisted men, led by SSgt. Nathan Rosenstein, came from the 1st

Infantry Division at Ft. Devens, Massachusetts.

The events at Pearl

Harbor on Sunday, December 7, 1941, had an immediate impact on base

activities. In a remembrance of Pearl Harbor day published in the

Manchester Union Leader in December 1993, retired Col. William A. Whelton

wrote of the unprepared posture of the base that fateful Sunday. All of

the bombs present were small practice weapons incapable of being used

effectively against an enemy, and there was no ammunition for the few

machine guns that were on base. In desperation, Whelton flew to Westover

Field where he hoped to find some ammunition. This lamentable situation

changed almost immediately when the first squadron of A-20 Havoc light

bombers arrived to equip the 45th Bomb Group following a 47-minute flight

from Mitchel Field, New York.

By December 15 large quantities of

live bombs were stored in the open at Manchester. The igloos for these

weapons were not scheduled for completion until the end of January 1942.

Ordnance personnel hastened to set up temporary bomb targets and a machine

gun range in New Boston. By February, construction of a permanent bomb

range was underway, with two of the three observation towers for range

control about to be erected. . In certain respects the Havoc aircraft were

unusual, as they were actually DB-7 export versions, originally intended

for France. This temporarily created a problem for base munitions

personnel, as the bomb suspension system had to be modified to make it

compatible with American bombs.

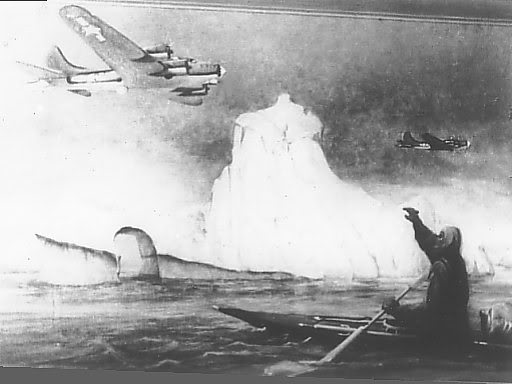

German submarines had begun to take

their toll of Allied shipping, and Manchester-based aircraft armed with

USN 325-lb. depth bombs participated in the search for the U-boats. The

stocks of bombs and ammunition on the base were growing rapidly. In fact,

the quantities of large demolition bombs exceeded the capacity of the

newly completed indoor storage and were placed in outdoor revetments. The

13th Anti-Submarine Squadron began operating from Grenier during the

summer of 1942 with B-25B & C Mitchel bombers and a number of Lockheed

B-34 Ventura aircraft. Typical patrol missions were 4-6 hours duration and

usually involved convoy escort off the New England coast. The aircraft

were normally armed with #325 depth charges. The 13th remained at Grenier

until September 1943, by which time the unit was also operating B-24D

Liberator bombers.

On February 22, Manchester Air Base was renamed

Grenier Field after Manchester resident 2Lt. Jean D. Grenier. A popular

athlete and graduate of the University of New Hampshire, Grenier had died

in the crash of an Army A-12 aircraft in Utah while flying a mail route on

February 16, 1934.The residents of the Manchester area had quickly become

familiar to the drone of the bombers operating out of Grenier Field, but

changes were soon to come. On May 16 1942, the 45th Bomb Group transferred

to Dover, Delaware, a move that came on the heels of the 717th Ordnance

Company's departure for Fort Dix, New Jersey. The airbase was still

growing in size and capability at this time. A new ordnance area had just

opened on the south side of the airfield, and armament personnel finally

had a suitable shop for handling guns and ammunition. New munitions igloos

allowed proper indoor storage of bombs for the first time, just as

ordnance personnel began to ship some of the base's stockpile of these

weapons to other airfields.

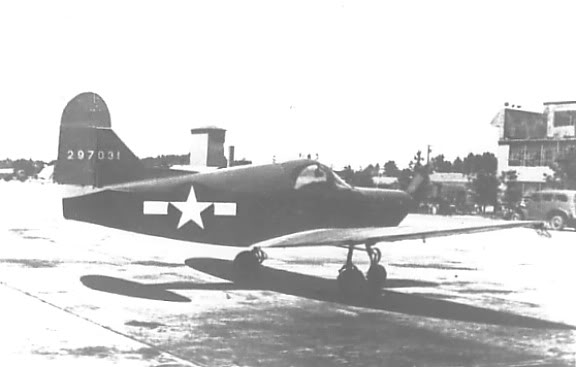

Grenier Field became involved in a

bold Army Air Force plan known as Bolero in June, 1942. Bolero was a code

name for the rapid buildup of American combat forces in England. Wartime

transatlantic crossings by multi-engine aircraft had become routine, but

the supply of fighter aircraft to England was a different matter. The most

common method of crossing had been as deck cargo aboard surface vessels.

Aside from being prohibitively slow and risky, this method exposed the

relatively delicate airframes to manhandling and the corrosive effects of

saltwater. An innovative plan was developed whereby the fighters would be

ferried across the ocean in a series of short hops with navigational

assistance provided by bombers. Most Bolero fighters departed from Presque

Isle AAF, Maine, but during June 1942, the 52nd Fighter Group began to

work up with Bell P-39 Airacobras at Manchester. Army Air Force leaders

soon decided the P-39 was not an ideal fighter for the European theater,

and the personnel of the 52nd went to England by ship. It wasn't until

late in the year, after being reequipped with the legendary Spitfire

fighter, that the 52nd began to operate from England as a combat fighter

group.

The 578th Army Air Forces Band proved to be very popular

throughout the greater Manchester area. Comprised of a full orchestra and

a swing dance band the military musicians highlighted many Army Air Force

recruiting drives in New Hampshire. Their itinerary included stops in the

New Hampshire capitol city of Concord, a North Country appearance in the

paper mill town of Berlin, and Bay State concerts in Boston and Ft.

Devens. Washington sent out requests for recordings from the band, and the

Grenier Field March, written by Assistant Conductor and clarinetist SSgt.

John Pastor was submitted. No evaluation of the music was ever returned by

headquarters, but this didn't faze the irrepressible musicians.

On

September 25, 1942, the Manchester Union-Leader, in cooperation with local

radio station WFEA, arranged for an overseas short wave broadcast of the

Grenier Field Band as part of the "For the Boys" concert series. In

October the band played at the 315th Fighter Squadron dance at the IOOF

hall in Manchester. (The 315th was equipped with Curtiss P-40s and trained

at Grenier for several months before departure to El Kabrit, Egypt as part

of the 324th Fighter Group). Other talent was in town as well. Dorothy

Lamour, a popular performer at the time who frequently accompanied Bob

Hope made a flight line stage appearance at Grenier.

The month of

July 1942 brought the inactivation of the 449th Ordnance Company, one of

the first Army Air Force units to arrive at Manchester. Many members had

already transferred out, leaving one officer and fifteen enlisted men who

were incorporated into the 34th Base HQ and Air Base Squadron. At this

time ordnance personnel assumed all motor vehicle maintenance

responsibility, which was previously handled by the Base Quartermaster.

The mettle of the ordnance personnel that remained was tested the

following month when they were required to support the bombing and

gunnery-training missions of a Heavy Bomb Group.

The recruiting

drives brought results, and large numbers of inductees arrived in

Manchester for basic training. Assigned to casual detachments, these

recruits were quickly introduced to Army Air Force life. Large numbers of

New England area women also arrived to be initiated into the Women's Army

Corps. The groups of trainees varied greatly in size, some casual units

were comprised of one or two hundred members, while others would exceed a

thousand. When the training was completed, these units would be assigned a

shipment number and depart the base in secrecy, usually headed for the

port of Boston on a troop train. The Boston and Maine rail line that

serviced the airbase maintained a busy timetable that offered sixteen

round trips per day. Some incoming personnel shipments had been trained

elsewhere, and while they often looked well-prepared on paper, officers at

Grenier quickly learned clothing and equipment deficiencies were

commonplace. Inspections were frequent, and in order to rectify the

equipment problems quickly, it was necessary for airbase personnel to

maintain a close relationship with the Boston Quartermaster, the source of

replacement goods.

Grenier AAF remained under the control of the

First Air Force at Mitchell Field, New York from mid-1942 to mid-1943. A

significant portion of the personnel and aircraft assigned to the Eighth

Air Force in England had passed through Grenier. The New Hampshire airbase

was making a huge contribution to the war effort, which in turn helped

open up the European Air Offensive on July 4, 1942. By the fall of that

year antisubmarine patrols off the New England coast had led to a marked

decrease in U-boat activity. By August 1943, the Navy had assumed

responsibility for most of the antisubmarine missions previously flown by

the Army Air Force. This resulted in a decline in flight operations at

Grenier, and shifted the base's mission to the training of recruits.

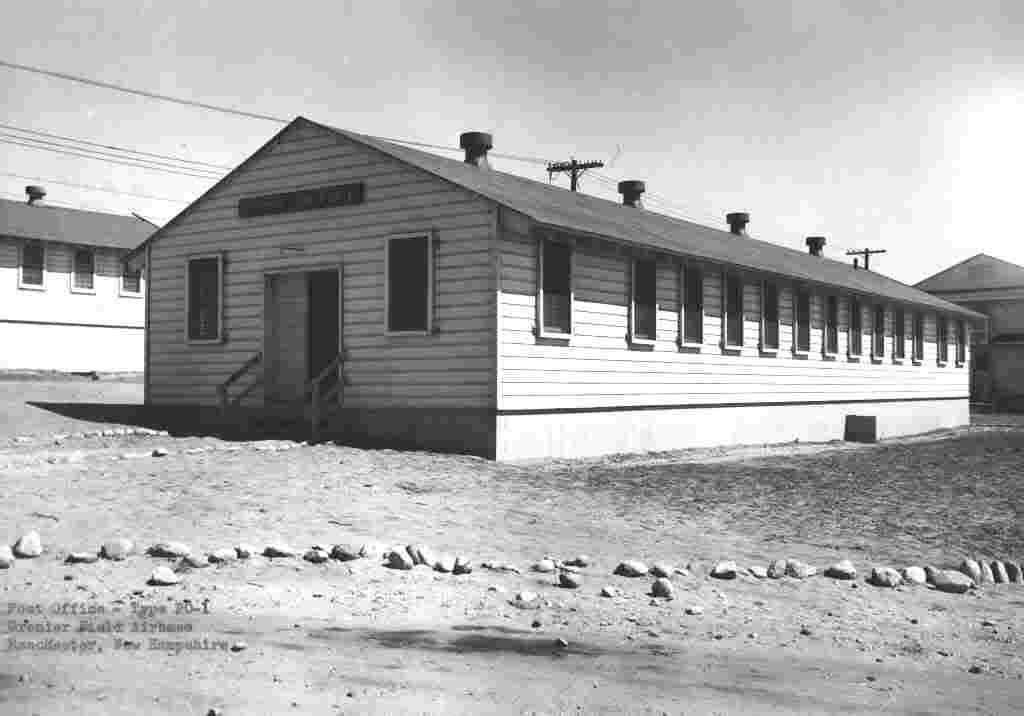

Air Transport Command (ATC) personnel visited Grenier on December

4, 1943, and recommended the North Atlantic Wing (NAW) relocate there from

Presque Isle AAF, Maine. The New Hampshire site offered several major

advantages over the previous location. There were three 150 foot-wide

paved runways at Grenier that ranged in length from 5500 feet to 7000

feet. The annual snowfall was considerably less than the Maine location,

and close proximity to the coast made it a convenient alternate landing

site for aircraft inbound from Europe. Manchester was not without

shortcomings. Only one of the six hangars at Grenier could properly

accommodate heavy bombers. No suitable building on base existed to house

the Wing headquarters section, so the Reconstruction Finance Corporation

offered the Hoyt Building at 497 Silver Street for this purpose. Known

today as the Silver Towers, this historical edifice still stands in

Manchester at that address.

Under the command of Colonel (later

Brigadier General) Lawrence G. Fritz, NAW operations began at Grenier

Field on January 1, 1944. Fritz had flown the North Atlantic route many

times as vice president in charge of operations at TWA, and was an

excellent choice for this position. Colonel John I. Moore, the original

base commander at Manchester, had been in Washington on detached duty

since August 1943. In Moore's absence, Colonel Roscoe C. Wriston took

command of the airbase, and eventually passed these responsibilities to

Colonel Marlowe M. Merrick. Grenier Field's main mission at this time was

to equip and process transient heavy bombers and aircrew for overseas

duty. Base personnel quickly aligned all of their efforts to support this

critical role. Manchester soon became an Aerial Port Of Embarkation

(APOE), and the first group of B-17s passed through the base on January

18. By the end of 1944, the North Atlantic Wing would supervise the

shipment of nearly 9000 tactical aircraft to Europe and Africa from bases

in the northeastern United States. A total of 170 B-17s arrived in

Manchester in February, by which time extreme cold along the Northern

Route had become a hazard. At Goose Bay, Labrador, fliers suffered

frostbite as they serviced their aircraft. The majority of these young

combat crewmen had recently trained at southern U.S. bases, and it became

the responsibility of instructors at Grenier to quickly educate them on

the hazards of winter flying.

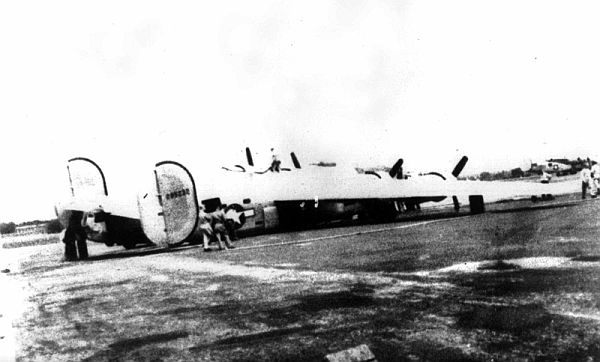

Mishaps affected a small percentage

of the aircraft that passed through Manchester. Some of these episodes

were humorous, while others were tragic. One B-17 pilot gave the bail out

order over Portland, Maine because of problems with the aircraft's

autopilot. Upon further diagnosis of the problem, the officer rescinded

the order, but the tail gunner had already hit the silk. After he landed

unhurt in the town of Northrup, Maine, the gunner returned to Grenier to

rejoin his crew for a less eventful departure. Disaster struck on April

24, when a B-24 took off from Manchester and crashed into Washtub Hill in

Epsom, New Hampshire, with the loss of all ten aboard. The New Hampshire

countryside would be the scene of other terrible crashes as hundreds of

the bombers droned overhead in the coming months. Transient combat

aircraft virtually poured into Manchester in June 1944. The monthly total

was 572 tactical aircraft arrivals, with a one-day high of 107. Of the 270

B-17s that arrived, the majority came from Kearny, Nebraska, while most of

the 189 B-24s came from Hamilton AAF, California, and Mitchel AAF, New

York. These bombers consumed 789,042 gal. of 100/130 octane aviation fuel.

Aircraft maintenance activities in support of these planes accounted for

22,800 man-hours. Grenier workers began to process U.S. Navy PBY

Catalinas, B-24s, and PB4Y Privateers for overseas duty, and this pushed

the July statistics far beyond those of June.

The Priorities and

Traffic Office (P&T) acquired the use of the Northeast Airlines

terminal on the north side of the airfield to expedite aerial movement of

priority cargo and passengers. Two C-46 flights were routed through

Manchester for this function. One flight ran from Newark, New Jersey to

Presque Isle AAF, Maine, and the other from Boston, Massachusetts to the

northern Maine base. The approach of a hurricane in September led to the

evacuation of many Grenier-based planes to Montreal. The only damage on

base occurred when a storage structure was toppled. During the storm, a

Navy F6F Hellcat fighter made an emergency landing in Rockingham, New

Hampshire. The aircraft was undamaged and the base recovery team simply

folded its wings and towed it to Grenier via highway. The Station Hospital

was very active from August to October 1944. Airbase medical staff gave

physicals to 16,128 transient airmen, and performed 84 emergency

surgeries. The station hospital assumed additional responsibilities when

Grenier became an Air Evacuee Center for wounded personnel enroute to

stateside hospitals from the European theater. The number of transient

bombers began to decline after September 1944. Base production shops

turned their attention to installation of bomb bay fuel tanks and weather

observation equipment in the B-17s and B-25s used by the 1st Weather

Reconnaissance Squadron. This unit was attached to the 8th Weather Region,

headquartered at Grenier.

As the winter of 1944-1945 approached,

cold weather again became a threat to flight crew safety on the Northern

Route. Frostbite among aircrew became such a serious problem at Goose Bay

that the Labrador airfield was temporarily closed. The cold weather also

began to plague the aircraft, especially the B-24 Liberator. Held at

Grenier due to cold weather landing gear malfunctions, shipments of these

bombers were soon redirected to southern routes. The winter of 1944-45

brought record-breaking snowfall to Grenier Army Air Field in Manchester,

New Hampshire. The season total was 73.4 inches, according to records kept

by the 8th Weather Region at the airbase. This was the most in a single

season since the airbase had opened, and according to local sources, the

most the Granite State had seen in many years. Snowplow crews worked hard

to keep the runways open to air traffic. In spite of these efforts, many

weather-related mishaps took place. On January 5,1945, a B-17 hit a

snowbank and lost its tail wheel during an attempted landing. As a

precaution, the crew jettisoned the bomber's ball turret into Lake

Messabesic while setting up for another approach. The pilot landed the

Flying Fortress without further problems. In a different incident, a B-24

pilot claimed his aircraft received damage due to an obstruction on the

runway. An investigation revealed a slightly different story. The

Liberator pilot had made a landing approach into the glare of the low

winter sun, and had put the big bomber down on the frozen ground between

the runway lights and adjacent snowbank! A blizzard arrived on February 7,

which added to the accumulated snow depths. The 135th Army Airways

Communications Service (AACS) detachment had worked to install a new

navigational and approach aids at the base radio range in South

Londonderry. They were unable to reach areas of the site due to snowdrifts

that exceeded a depth of 10 feet. The airbase sent down a bulldozer and a

"Snogo" rotary plow to open up the access road to the radio

shack.

The processing of tactical aircraft at Grenier Field had

peaked during the summer of 1944, but there was still a substantial flow

of bombers enroute to the European and Mediterranean theaters. Unusual

aircraft occasionally showed up, as on February 23, when General

Eisenhower's personal YC-108 transport arrived. This VIP aircraft,

modified B-17F 42-6036, departed for Stephenville, Newfoundland the

following day. The newest in transport aircraft arrived two days later

when a Lockheed C-69 Constellation flew in from Washington National

Airport. The sleek aircraft was given a close look by members of the North

Atlantic Division (previously North Atlantic Wing), who were treated to an

impressive aerial demonstration by the large aircraft in the

afternoon.

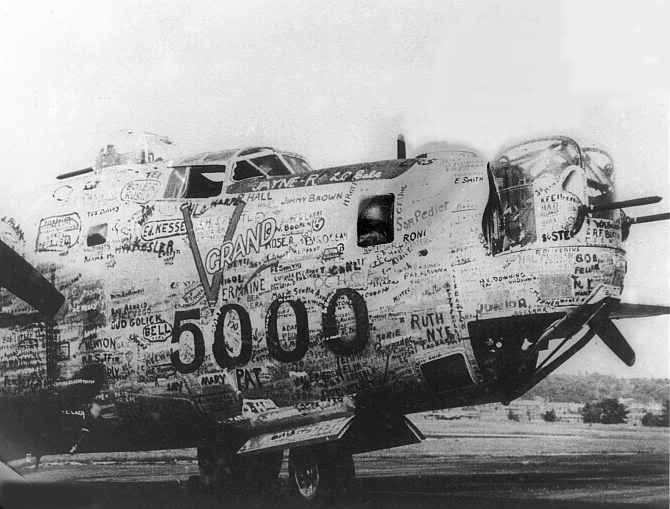

By the end of March, 5,447 heavy bombers had passed

through Manchester since the beginning of NAW operations 15 months

earlier. Processing the 51,000 crewmen aboard these aircraft was a huge

task. Many of the crewmen were given physical exams by base medical

personnel. The staff at Grenier briefed the fliers on a wide range of

operational subjects such as cruise control, ditching at sea, navigation

techniques and radio procedures. Electrically-heated flight suits and box

lunches were issued to all. The aircraft needed preparation also. Engine

maintenance accounted for many thousands of man-hours. Flight controls had

to be rigged and hydraulic leaks repaired while machine gun ammunition and

other combat gear was taken aboard. For many of the aircraft the list of

maintenance discrepancies was long.

March 10, 1945 marked the

arrival of 37 aerial evacuees, the first since October of the previous

year. Grenier medical staff provided care for the casualties, and placed

them aboard C-47 transports for airlift to hospitals throughout the

country. Though officially downgraded to dispensary status, the airbase

hospital would process many of these cases in the coming months.

Although the airbase staff did their best to be hospitable to

those who passed through, the experience of the transient crews was no

picnic. The men were restricted to the base and not allowed to use the

telephone. Most of them passed their spare time by writing letters or

shopping at the Post Exchange. A few signed out athletic equipment and

engaged in sports activities. Virtually all of the men quickly realized

that the airbase had a sizable population of WACs. There were several

well-attended dances at the club every week.

On April 7 Manchester

received a message that alerted base personnel of significant change in

the near future. All B-17s and B-24s not equipped with radar were to

return to their point of origin. Bombers with radar were to proceed east

with flight crew only, while bombardiers and gunners were to debark at

Grenier. By the end of April, a subsequent directive grounded all

eastbound tactical movements. On April 26, in compliance with the earlier

directive, a group of bombers departed on a reverse course, back to bases

in the Western United States.

An OTU (Operational Training Unit)

for C-54 crewmen was activated at Grenier on May 7. Five Skymaster

transports were assigned to the school. The OTU enjoyed a very brief

existence. August 13 was the date of the final class. In that short time

span 53 first pilots, 50 co-pilots, 29 navigators and 67 aerial engineers

learned the trade of transport crewmen in New Hampshire skies. The latter

group included 9 members of the Royal Air Force.

A manning problem

developed at Air Transport Command (ATC) headquarters in the spring of

1945. Many troops of the command had served overseas for long periods and

were due for rotation to stateside airfields. At Grenier, the majority of

troops had not performed overseas duty. There were 1,402 men and women in

uniform at Manchester at the end of April. Two weeks later, NAD ordered a

rotation plan into effect that sent 500 Grenier troops to overseas

assignments, and another 500 to duty elsewhere in the Continental United

States. This resulted in skill shortages and personnel imbalances at the

airbase. A rumor declaring that Grenier Field was on the verge of

inactivation quickly surfaced. A political controversy broke out between

Maine and New Hampshire as each state fought to make its respective

wartime airfields into permanent peacetime installations.

The

personnel problems at Grenier struck the base just as the Army Air Force

announced it would fly 4,000 aircraft back to the United States as part of

the White Project plan. Manchester was tasked with operational control of

nearly all these westbound flights, many hundreds of which touched down at

Grenier.

During July, airbase leaders made plans to launch Green

Hornet Airlines. This C-54 operation was to follow a

Grenier-Azores-Stephenville-Grenier route. The idea had a short lifespan

however, and the flights operated for just 12 days in early August. Later

that month, ATC permanently dispatched the C-54s to the west coast to make

them available for use in the Pacific.

The level of activity at

Manchester declined steadily. On August 13, headquarters eliminated the

long-standing C-46 flights from Boston and Newark. Another decision led to

the inactivation of the C-54 OTU on the same unlucky date. Operation of a

small fleet of C-47 transports to the other NAD airbases became the

primary mission at Manchester. The workweek of civilian employees was

reduced from 48 to 40 hours in September, and the possibility of a layoff

loomed ahead. Many of the newly-assigned military people needed housing

for their families, but in the tight local housing market it was a

difficult task. As this situation worsened, the incoming troops were told

not to bring their families to Manchester.

An uncertain future lay

ahead for many of the nation's wartime airfields, including Grenier.

Beginning as early as 1943, military leaders had discussed the need for

the formation of National Guard and Reserve flying units following the

termination of hostilities. Manchester eventually became home to units of

the Air National Guard and Air Force Reserve. Grenier would host many

summer encampments for these reserve units. Even as these peacetime plans

for Grenier were being made, the emergence of the USSR as a nuclear power

affected the airfield's immediate future. The United States Air Force,

which had just been granted status of a separate branch of the armed

forces, was tasked with the need for tremendous expansion to meet the

perceived Communist threat. Grenier Air Force Base became host to the

first of New England's many Strategic Air Command units. These

developments and the use of the Manchester Airport in the postwar era will

be covered in a future article.

THE END

More Grenier Field

Articles and photos

|